These artworks, like their outdoor counterparts, ask how we use vision and movement to make sense of our worlds; to make invisible phenomena visible and palpable; and to collect knowledge, engage in critical reflection, and construct cultures and worlds based on the stories that we live each day.

The Curious Desert: Indoor Works

On View Until 27 July

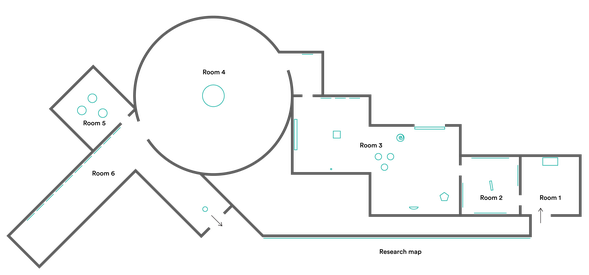

The exhibition includes a series of meditative light installations, geometric models, photo series, watercolours and a sprawling research map inside the National Museum of Qatar.

Share with a friend

A schematic floorplan of the exhibition's indoor galleries

Room 1

The artwork Your sooner than later, 2020, greets you to The curious desert. This radically analogue film, as the artist calls it, develops and vanishes in a slow continuum of ever-changing shapes, colours, light, and shadows, appearing constantly new. The origin of the light and the objects that produce the patterns – motors, mirrors, filters, and lenses – are visible behind the screen. Eliasson has long been fascinated by optical devices. Over the years he has collected many lenses as part of his investigations into perception and the qualities of light. The lenses in this artwork have been removed from their normal use as instruments of observation and recording. Instead, they have been treated as material to create something of beauty. The artwork is dependent upon the physical encounter between you, the viewer, and the artwork in the here and now.

‘My artworks strive to embody transformation rather than stability and being’, the artist writes. The curious desert ‘is not a stable representation or a model of reality; it is reality. Your experience of it changes with the time you spend in it’.

Olafur Eliasson. Your sooner than later, 2020. Projection screen, LED spotlight, lenses, colour-effect filter glass, concave glass mirror, mirror, aluminium, brass, steel, motors, control unit. 270 x 270 x 120 cm. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Ali Al Anssari

Olafur Eliasson. Your sooner than later, 2020. Projection screen, LED spotlight, lenses, colour-effect filter glass, concave glass mirror, mirror, aluminium, brass, steel, motors, control unit. 270 x 270 x 120 cm. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Room 2

Over the years, Eliasson has returned again and again to Iceland, the country his family is from, in order to explore the its cultural and natural landscapes with his camera. This ongoing, ambitious venture – almost cartographical in its scope – has resulted in approximately eighty photo series to date and a wealth of individual photographs of glaciers, waterfalls, rivers, volcanoes, and caves, among other things. He displays the photo series in grids, as typologies, each devoted to a specific element of the country’s environment. Often the same phenomenon is recorded in various settings, or else a single object is documented from different perspectives. This approach emulates a quasi-scientific taxonomy and comparison among specimens – not as the only way of engaging with the subject of the image but as one approach to it and how we relate to it.

Far from merely documenting the terrain, Eliasson’s vibrant images reflect on our relationship to nature, the physical spaces in which we exist, and the body’s felt motion through space.

The series exhibited here were selected by the artist with the landscape of Qatar in mind. He sees a particular productive juxtaposition between the location of Iceland and Qatar, both of which exist at environmental extremes. ‘Although they could not be more different, the sandy landscape of Qatar and the lava fields of Iceland’, Eliasson says, ‘are in a certain sense connected. They both experience extreme temperatures; they are both deserts. They are both fragile and vulnerable landscapes.’

Olafur Eliasson. Left wall: The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019. 30 C-prints; Right wall: The inner cave series, 1998. 36 C-prints. Ceiling: Adrift compass, 2019. Driftwood, magnets, paint (blue, black, yellow, white). 38 x 134 x 24 cm. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson. The glacier melt series 1999/2019, 2019. 30 C-prints. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Room 3

The sculptural works exhibited in this gallery reflect many of the central themes of Eliasson’s artistic practice over the years. The shapes and forms derive from the on-going geometrical research conducted by the artist together with his team at Studio Olafur Eliasson, in Berlin, Germany. Eliasson’s interest in these complex forms – in polyhedrons, spheres, and curves – stems from a desire to find alternatives to the dominant, orthogonal thinking of modern architecture, art, and design. New models of design and construction, he hopes, can counteract the numbing of our senses. Light plays an important role in his artistic practice as well, since it is the very condition of visual perception. The quality, tone, and intensity of light fundamentally affect how we see and respond to the world. Presented together in The curious desert, these artworks ‘speak’ not only individually but also across the gallery space to one another, each model-like artwork adding contextual resonance to its neighbour.

Situated in front of a window at one end of the gallery, Algae window, 2020, is a composition of glass spheres of various sizes. The artwork closely resembles the structure of one type of the single-celled algae known as diatoms. Found around the world in oceans and waterways, these tiny organisms produce a great deal of the planet’s oxygen and remove large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere. They are characterised by complexly patterned frustules, or shells, made out of silica, which exhibit exquisite symmetry and geometrical complexity. The artwork was inspired by Eliasson’s interest in the more-than-human, a major topic explored in the research map.

Olafur Eliasson. Left to right: The complete sphere lamp, 2015; The presence of absence (Nuup Kangerlua, 24 September 2015 #2), 2016; Faint memory map, 2022; Faint expectation map, 2022; Solar empowerment spiral, 2016; Algae window, 2020. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson. Algae window, 2020. Glass spheres, steel, aluminium, plastic, paint (black). 380 x 350 x 80 cm. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson. Left to right: Power tower, 2005/2023; Eye see you, 2006; The complete sphere lamp, 2015; Solar empowerment spiral, 2016. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson. The slow life of sunlight, 2023. Coloured glass (pink, pink fade, yellow, light yellow, yellow fade, light green, green fade, blue fade, purple fade), silver, driftwood. 116 x 405 x 15,5 cm. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Ali Al Anssari

Room 4

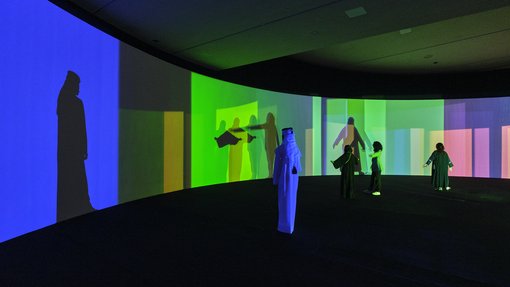

Broad bands of colour crawl across the walls of this circular room, wrapping visitors in a vibrant installation of ever-changing fields of light. The circular construction responsible for The living lighthouse, 2023, contains panes of coloured glass, colour filters, and shutters that turn steadily on motors as they are illuminated by spotlights from within. The colourful shadows move along the walls, overlap, and give rise to secondary and tertiary hues. Visitor’s silhouettes dance among the waves of light and colour, causing new shades and forms to cascade about the room. The disorienting curtain of moving light incorporates the walls and surrounding space into the artwork, transforming the exhibition gallery from a container for art into an object of attention in itself.

This 360-degree light installation connects to the outdoor artworks located near Al-Thakhira Mangrove Nature Preserve, especially to the Orientation lights for rising seas, 2023, a group of five lamps distributed among the twelve pavilions whose directional lights divide the landscape into distinct light regions.

Olafur Eliasson.The living lighthouse, 2023. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson.The living lighthouse, 2023. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Room 5

Each of these three, related artworks – Object defined by activity (now), Object defined by activity (soon), and Object defined by activity (then) – consists of a small water fountain erupting directly from the black, cylindrical plinths. Stroboscopic lamps, placed immediately above the plinths, illuminate the jets of water in rapid, rhythmic bursts of light, producing the illusion of static sculptures suspended fleetingly in mid-air.

Akin to the way photography arrests the fluidity of passing time and the continuity of motion, these stroboscopically illuminated fountains provide a glimpse of the impossible space of the present. The resulting shapes reveal the curves and geometry underlying the movements of the water in gravity, relating aesthetically to the geometrical sculptures and the chance drip paintings on view in the other galleries.

Olafur Eliasson. Object defined by activity (then), 2009. Water, stainless steel, foam plastic, plastic, pump, nozzles, strobe light. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson. Object defined by activity (then), 2009. Water, stainless steel, foam plastic, plastic, pump, nozzles, strobe light. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Room 6

The circular artworks exhibited in this gallery were created by simple machines installed in Eliasson’s outdoor artistic laboratory, near the Al Thakhira Mangrove Forest. The works were created by machines housed in three separate pavilions at the site. Solar-drawing observatory (Large spheres) and Solar-drawing observatory (Small spheres) use sunlight and lenses to burn marks on steadily rotating sheets of paper, while Saltwater-drawing observatory comprises two machines that mix lagoon water with pigment and pendulums driven by the wind.

The artist has been creating drawing machines since 1998, a project he began in collaboration with his father, Elias Hjörleifsson, who was an artist, sailor, and cook. Eliasson’s drawing machines generally use ink, paint, or coloured pencils and are controlled by aleatory elements, such as natural phenomena or vibrations from sound waves or motion, to create markings on circular sheets of paper or canvas.

Olafur Eliasson. Drawings from outdoor pavilions, 2022. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Olafur Eliasson. Drawings from outdoor pavilions, 2022. Installation at the National Museum of Qatar, 2023. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Outdoor Works (On View until 28 October)

In addition to the works on view at the National Museum of Qatar, The curious desert includes a series of twelve outdoor pavilions near the Al Thakhira Mangrove Nature Preserve.

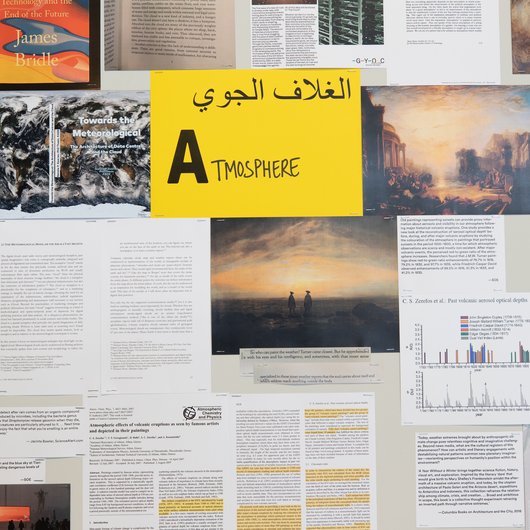

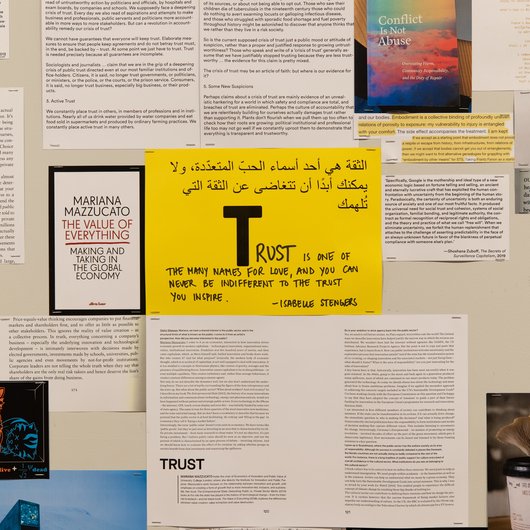

Research map

The Research map – an artwork in progress – was once a pin board of ideas, no more than a few square metres in size, used by a few members of Studio Olafur Eliasson. As it became more central to Olafur Eliasson’s thinking, he decided to create several expanded versions of the pin board for museum visitors. Over time it has grown to some thirty-five metres in length through the multi-year work of the studio research team. Despite its vast scope here at the National Museum of Qatar, the Research map is not, and does not aspire to be, comprehensive or complete.

Although it is organised alphabetically by concepts, the Research map is meant to be approached non-linearly. You can start anywhere along the wall you like. It is a space of micro-storytelling, where seemingly unrelated contents vibrate next to each other and create new meaning. We hope you, visitor and reader, bring your own views and associations to the map.

1 / 26

Atmosphere + Anthropocene

Atmosphere concretely refers to the layer of gases that envelops and supports life on Earth, but it can also describe an ephemeral feeling that one gets from a space or situation – for example, the atmosphere of a dinner party, or a country’s political atmosphere – and is a term closely linked to aesthetics. The geographer Derek P. McCormack, for example, defines atmospheres as ‘elemental spacetimes that are simultaneously affective and meteorological, whose force and variation can be felt, sometimes only barely, in bodies of different kinds’.

Recent studies linking the depictions of skies in historical paintings with the atmospheric conditions at the time of their creation have uncovered an intriguing link between the two notions of atmosphere: paintings produced after a major volcanic eruption in the 1880s contain altered colour ratios in their skies, exhibiting more reds than greens in comparison to paintings made in other years. The aesthetic mood of these paintings is largely invoked by the sun acting upon suspended ash.

Similarly, volcanically induced atmospheric conditions during that same period likely inspired Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein: ‘Written amid a mysterious climate crisis, remembered as the Year Without a Summer, the novel registers the unpredictable impact upon the literary imagination of an atmosphere in disarray.’

The idea of making something invisible – like air – explicit and felt has inspired Olafur Eliasson extensively in his art-making.

Like fish swimming in water, humans are not always aware of the air that surrounds us. Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk suggests that the air of our atmosphere was not explicitly felt until it was weaponised during World War I through poison gas attacks; air was taken away and soldiers were left to suffocate in the trenches. According to the sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour, Sloterdijk’s idea is that ‘if you want to understand what it is to feel something, it’s not by rehearsing the tired old scenography of empiricism . . . Feeling is more roundabout; it’s the slow realization that something is missing.’ The air became part of ‘our collective, political attention’ at the point at which it could be taken away from us.

Over 100 years later, as air pollution causes the most damage to the world’s most vulnerable human (and non-human) populations, this notion continues to resonate in discourses around climate justice and the Anthropocene. Proposed in the 1980s by ecologist Eugene Stoermer, the Anthropocene is a name for our current geological age that conceptualises it as having been defined by human activity. Confronting the Anthropocene entails asking ourselves ‘how we can live on a damaged planet’, as the anthropologist Anna Tsing proposes.

Another crisis of breathlessness has entered international conversation in recent years following the murder of Eric Garner – a Black man who was also a father, grandfather, and horticulturalist – by a police officer; his final words, ‘I can’t breathe’, were taken up as a Black Lives Matter rallying cry.

Sources

Derek McCormack, Atmospheric Things: On the Allure of Elemental Envelopment (Durham, NC, 2018).

Dehlia Hannah, ed., A Year Without a Winter (New York, 2019).

Bruno Latour, ‘Air’, in Sensorium: Embodied Experience, Technology, and Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA, 2006).

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, 2021).

Leah Thomas, ‘“I Can't Breathe” and the Inextricable Link Between Climate and Racial Justice’, Elle, 3 September 2020, https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/a33905037/i-cant-breathe-police-brutality-covid-19-climate-crisis/

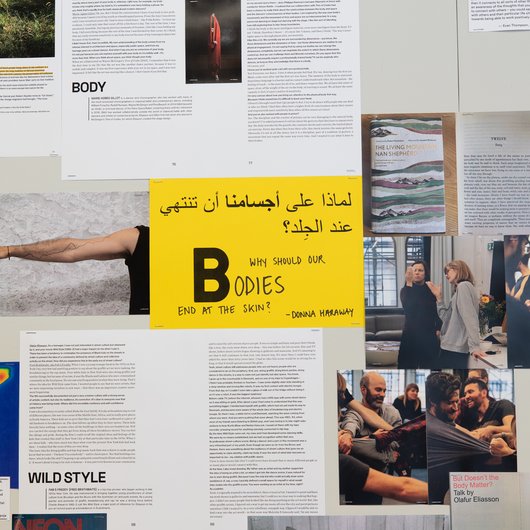

2 / 26

Bodies

There are as many worlds as there are different bodies, with all possible differences in gender, age, race, and abilities – making bodies and worlds necessarily plural. It is easy to talk about ‘the body’ as an abstract, abled form, but it is reductive, it neglects difference, and it does not acknowledge the countless unique lived experiences of people, let alone non-human beings. In previous editions of the research wall, we used ‘Body’. We are happy to have now made the move from ‘Body’ to ‘Bodies’.

Artist Shannon Finnegan’s Portable Mural, 2018, consists of a single sentence arcing across a wall: ‘Reinventing the strangeness of my movement as an art form that only I am the perfect practitioner of.’

Questions of accessibility need to be brought into exhibition making and planning, argues Andrew Miller, the U.K. government’s disability champion, in an Artsy article: ‘The institutional thinking around disability is not advanced enough. . . . Visual arts have got quite a long way to go.’

Olafur Eliasson’s artworks have long been inspired by the artist’s experience of his own body. This interest, which he first developed as a breakdancer in his teenage years, testifies to his particular affinity with dancers and choreographers, like the choreographer Yvonne Rainer, street dancer and choreographer Steen Körner, and the ballet dancer Marie-Agnès Gillot, who says, ‘I think the body is the most intelligent material, even more intelligent than the head. It is not “I think, therefore I dance” – it is more like “I dance and then I think.” The way I investigate a space is through physicality, not mentally.’ It is an approach that can be traced to the European avant-garde of the early twentieth century, to artists like Oskar Schlemmer and dancers like Rudolf von Laban, who investigated the way bodies create spaces through movement. Laban wrote that ‘movement is more or less living architecture, living through changes of position but also through cohesion’.

In addition to creating space, our bodies are also porous – we touch the world and integrate the outside via our breathing. In the words of the science writer Tor Nørretranders, ‘When you take a breath you touch a part of the planet with the inside of your body.’

Historian of science and technology Michelle Murphy has written on the ‘the chemical relations of our embodiment’, looking in particular at pollution, ‘decolonial senses of embodiment’, and knowledge-making. We have been inspired by their take on embodiment and try to think along with these ideas. They write: ‘Embodiment is a collective binding of profoundly uneven relations of porosity to exposure: my vulnerability to injury is entangled with your comfort.’

Sources

Marie-Agnès Gillot, in conversation with Olafur Eliasson, ‘Body’, in Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life (London, 2019).

Claire Voon, ‘How Museums Are Increasing Accessibility for Visitors with Disabilities’, Artsy, 14 October 2019, online at https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-museums-finally-accessibility-visitors-disabilities-seriously.

Tor Nørretranders, quoted in Olafur Eliasson: Never Tired of Looking at Each Other – Only the Mountain and I (Beijing, 2012).

Michelle Murphy, ‘What Can’t a Body Do?’ in Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 1, no. 3, 2017.

3 / 26

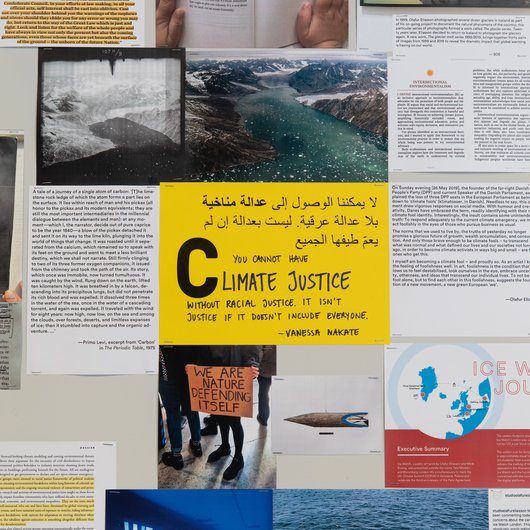

Climate Justice

‘It’s not the human species in general that has caused climate change’, says art historian and cultural critic T. J. Demos. ‘It’s particular humans, it’s particular corporations and developed nations within a long history of capitalism, of colonialism, of slavery, of genocide, and that has to be brought into the conversation.’ Although the crisis affects the entire world, Demos continues, ‘climate change affects different people differently, depending on geographical location as well as how climate change intersects with wealth or poverty, class, gender, religion’. The poorest communities tend to be harmed the most by climate change, and they are the ones least responsible for creating it. The term climate justice acknowledges the intersectionality of climate change, the way in which multiple forms of discrimination, racism, and gender inequality overlap and combine to affect some people and communities more than others.

According to the former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson, ‘Women and people from what we’re calling the Global South really do suffer most and first from the adverse effects of climate change, so they’re the ones finding the solutions. . . . It’s women from the Global South, indigenous women, women from minority groups, and women in general who are just rolling up their sleeves and getting on with it.’

For humans to respond to climate change, it cannot remain an abstraction about a hypothetical future. We must recognise it as a paradigm shift whose consequences are being lived out by real people and non-human beings in the present. This crisis is having immediate, local, palpable effects on the life-worlds of individuals and communities who have names and faces and who do not always have agency. Climate change as a global emergency is deeply material, specific, and embodied.

Olafur Eliasson’s artwork Ice Watch aimed to make the experience of climate change tangible by bringing large blocks of ice from the waters off the coast of Greenland to people living in cities far away. In the artwork’s multiple iterations, the Arctic ice slowly melted over the course of weeks in the public squares of Copenhagen, Paris, and London – national capitals that are the seats of government decision-making around climate change. Eliasson hoped that people’s direct, intimate experiences of the melting ice blocks would evoke immediacy and drive climate action.

How do we deal with the finite pool of attention and the sense of numbness that pervades our society in the face of the climate crisis? What does it take to spur action? As journalist David Wallace-Wells remarks, ‘We have a tendency to wait for others to act, rather than acting ourselves; a preference for the present situation; a disinclination to change things; and an excess of confidence that we can change things easily, should we need to, no matter the scale.’ At the same time, sociologist Daniel Aldana Cohen argues, ‘These struggles are actually going pretty well. Call it invention, call it care, call it politics – climate change is the story of people fighting over how to live.’

Sources

T. J. Demos, ‘Against the Anthropocene’, lecture at Kaaitheater, Brussels, 2017.

David Wallace-Wells, ‘Time to Panic’, The New York Times, 16 February 2019.

Daniel Aldana Cohen, ‘Apocalyptic Climate Reporting Completely Misses the Point’, The Nation, 2 November 2018.

Mary Robinson, ‘Mothers of Invention’ podcast, July 2018.

Rebecca Solnit, ‘Woolf’s Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable’, The New Yorker, 24 April 2014.

4 / 26

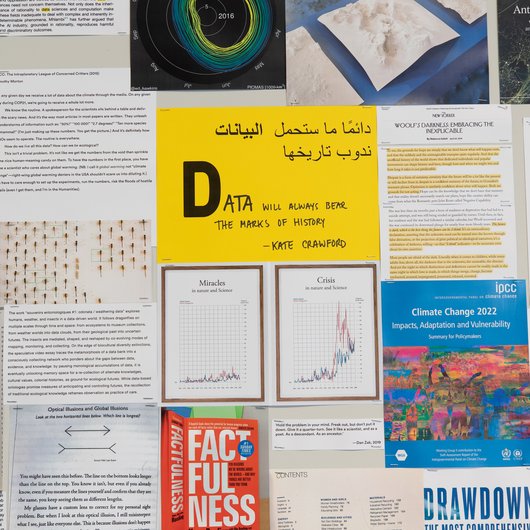

Data

Today we have access to, are exposed to, and even ourselves produce reams of data – information that can be both helpful and harmful, and even traumatising. Caroline A. Jones asks, ‘How do we bridge . . . into a world in which so much of the data comes from things we can no longer see, hear, smell or feel – and a world in which the average human has not yet evolved to understand deep time, not to mention statistical models of causality for anthropogenic climate change?’

One way of attempting to bridge into this world is through images. How do we visualise data and information to make it understandable for a broader public, especially when it comes to motivating action in response to the climate crisis? Scientists like Ed Hawkins and designers like Xandra van der Eijk have been working intensively on these questions. Van der Eijk’s 3D scans of a receding glacier deal with climate grief, and Ed Hawkins has created a number of models for visualising the changes in global temperatures over time.

The work of physician and statistician Hans Rosling shows that people are notoriously poor readers of data, which, he argued, gives us a faulty view of the world and the problems facing us. Instead, he was in favour of only holding opinions that can be backed up by the data, a position he termed ‘factfulness’.

Social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff sees data – and its ownership and commercialisation – as a distinctly political issue, integral to what she has dubbed ‘surveillance capitalism’: ‘a new subspecies of capitalism in which profits derive from the unilateral surveillance and modification of human behavior. . . . The game is selling access to the real-time flow of your daily life – your reality – in order to directly influence and modify your behavior for profit’. Olafur Eliasson is interested in examining our daily realities, not for data extraction purposes, but because they consist of lived experiences that offer potential for exploring notions of trust, reciprocity, agency, self-criticality, and sensory engagement.

The information we collect and analyse and how we use it is permeated by biases and often misapplied, as journalist and feminist Caroline Criado Perez shows in Invisible Women. For example, ‘Because women’s heart attacks may not only present differently, but may in fact be mechanically different, the technology we’ve developed to search for problems may not be suitable for female hearts.’ This misapplication of data is also present in the American justice system, where algorithmic software intended to give objective forecasts of criminality has been proven to reinforce structural racism in what is called ‘machine bias’. ProPublica, an organisation dedicated to investigative journalism, ran a statistical analysis of the software that revealed considerable bias: ‘The formula was particularly likely to falsely flag black defendants as future criminals, wrongly labeling them this way at almost twice the rate as white defendants. White defendants were mislabeled as low risk more often than black defendants.’

Sources

Caroline A. Jones, ‘Q&A: Caroline Jones on Cognitive Neuroscience and the Arts’, Arts at MIT website, 28 August 2014, online at https://arts.mit.edu/qa-mit-professor-caroline-jones/

Shoshana Zuboff, ‘The Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 5 March 2016.

Caroline Criado Perez, Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men (London, 2019).

Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, and Lauren Kirchner, ‘Machine Bias’, ProPublica, 23 May 2016, https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

5 / 26

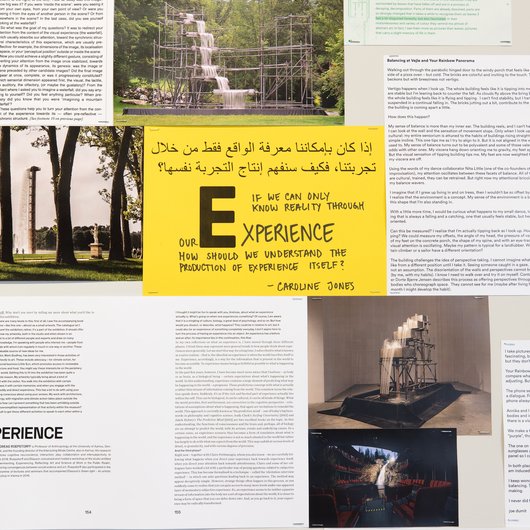

Experience

Philosopher Claire Petitmengin argues that ‘the loss of contact with our lived experience [is] the main root of the malaise that affects our society’.

Anthropologist Joe Dumit describes the urge to compare an experience with the images recorded by his phone: ‘The phone sees colors that I don’t. It sees radical differences and mine are muted. This is a dialogue. . . . The phone always has its own interpretation.’

But what is an experience? Is it simply a passively received set of percepts from outside, or do we, who are experiencing, contribute a great deal more than just interpretation of the outside world to the experiences? Scientist Andreas Roepstorff looks at various ways of answering this question and discusses his work together with Petitmengin on directing ‘your experience back towards experience itself . . . your attention back towards attentiveness’. Together with Roepstorff, Olafur Eliasson is leading a collaborative project between science and art, titled Experimenting, Experiencing, Reflecting (EER).

As part of this research, Eliasson has invited Katrin Heimann, a philosopher, to conduct ‘microphenomenological’ interviews at some of his recent exhibitions, such as Life in Switzerland. In interviews, participants are led through a series of questions to recollect and reflect on their recent experiences.

At the same time, as journalist Naomi Rea writes, ‘Experience has become a buzzword in marketing – and now it’s museums’ favorite noun, too. . . . Experiential art stretches back to the Happenings of the 1960s, when artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Allan Kaprow began creating in-person, difficult-to-commodify experiences that – ironically – were intended to thwart the market.’ Now experience – with its attendant ‘Instagrammability’ – is more for sale than ever. Even so, it still holds the potential for empowerment and subversion.

Sources

Claire Petitmengin, ‘Coming into Contact with Experience’, in Studio Olafur Eliasson: Open House (TYT Vol. 7) (Cologne, 2017).

Joseph Dumit, ‘Balancing at Vejle and Your rainbow panorama’, unpublished, 2019.

Andreas Roepstorff, in conversation with Olafur Eliasson, ‘Experience’, in Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life (London, 2019).

Naomi Rea, ‘As Museums Fall in Love with “Experiences”, Their Core Missions Face Redefinition’, Artnet.com, 14 March 2019 https://news.artnet.com/art-world/experience-economy-museums-1486807

6 / 26

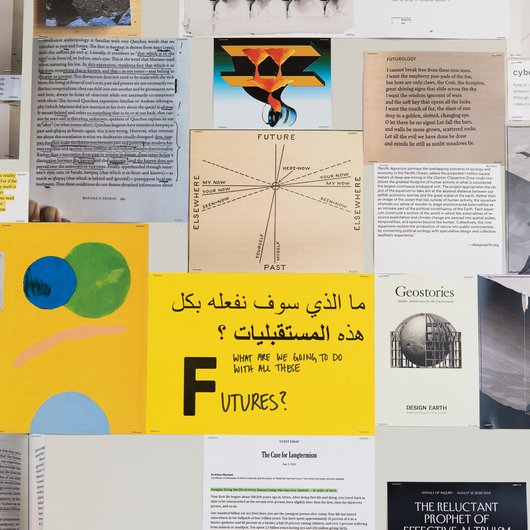

Futures

What will the future be like? If ‘we have never been modern’, as philosopher and sociologist Bruno Latour argued, then is the future synonymous with progress, or something far less linear, as anthropologist Marisol de la Cadena has proposed? In her discussion of two words from the indigenous Andean language of Quechua – ñawpaq and qhipaq (conventionally translated as ‘past’ and ‘future’ in English) –La Cadena writes: ‘First, ñawpaq does not make a distinction between past and present that modern history requires; and second, these notions do not follow modern directionality. Rather than a succession from past to present to future, these terms house a distinction between the known and the unknown, and the known does not prevail over the unknown or vice versa.’

What can indigenous cosmologies tell us about where we’re coming from and where we’re going? And, in the spirit of plurality, does it make sense to speak of one, monolithic future, or are there not rather multiple futures? Artist Miriam Simun asks, ‘If we exist in millions of completely disparate presents, why should suddenly our future be singular, objective, general, all-encompassing? Standardized futures are like standardized styles: colonizing and homogenizing.’

How will we, the inhabitants of spaceship Earth, respond to the continuing challenges of the climate crisis? Will we do what needs to be done to reduce our emissions? Will we remake the planet through geoengineering? Science writer Oliver Morton believes that ‘imagining geoengineered worlds that might be good to live in, in which people could be safer and happier than they would otherwise be, is worth doing’. Or are dreams of technological solutions, and specifically carbon capture, quite literally a waste of energy? Environmental engineer Charles Harvey and entrepreneur Kurt House argue precisely that: ‘What the technology [of carbon capture] also does is allow for the continued production of oil and natural gas at a time when the world should be ending its dependence on fossil fuels.’

Or, if we don’t act now, will we, as the curator Paola Antonelli argues, go extinct? ‘Extinction is normal, it’s natural’, she maintains. ‘We don’t have the power to stop our extinction but we have the power to make it count.’

The science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin writes in her poem ‘Infinitive’: ‘With or without us / there will be the silence / and the rocks and the far shining.’

Upon the declaration in 2019 of the extinction of the 700-year-old glacier Ok, in Iceland, activists and mourners decided to mount a plaque at the site to commemorate its passing. The dedication on the plaque, addressed to future generations, reads: ‘This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.’

If we are the ancients to a future someone, if we are living in the distant past of future people, then, as philosopher William MacAskill suggests, are future people ‘the true silent majority’? And the question follows, what kind of ancestors do we want to be?

Sources

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, MA, 1993).

Marisol de la Cadena, Earth Beings (Durham, 2015).

Miriam Simun, ‘What Are We Going to Do with All These Futures?’, in Training Transhumanism (I Want to Become a Cephalopod), thesis (MIT, 2018).

Oliver Morton, The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World (Princeton, 2016).

Paola Antonelli, ‘“We Don’t Have the Power to Stop Our Extinction” Says Paola Antonelli’, Dezeen, 22 February 2019.

Andri Snær Magnason, ‘A Letter to the Future’, plaque for Ok glacier, August 2019.

Ursula K. Le Guin, ‘Infinitive’, in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene (Minneapolis, 2017).

William MacAskill, ‘The Case for Longtermism’, The New York Times, 5 August 2022.

7 / 26

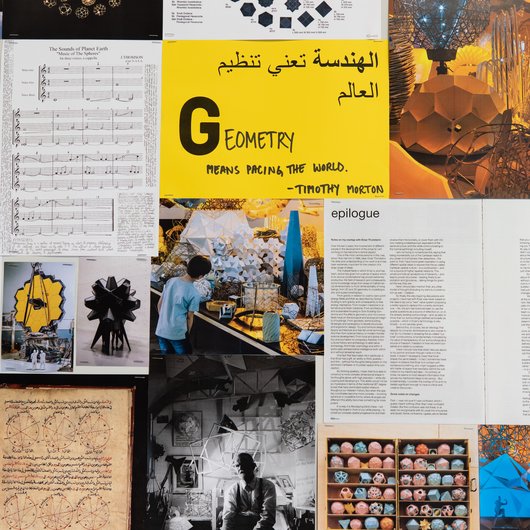

Geometry

Inspired by utopian architects like R. Buckminster Fuller and Frei Otto, Olafur Eliasson conceived his first geodesic structures and geometric works in the early nineteen-nineties. To realise these works, he contacted the Icelandic mathematician and architect Einar Thorsteinn. In a collaboration that lasted until shortly before Thorsteinn’s death in 2015, the two developed – along with other members of the studio team – numerous artworks and pavilions that employ geometry both structurally and as a visual language. Most notably, they explored fivefold symmetrical patterns and shapes in works like 5-dimensionel pavillon (1998) and later – together with Eliasson’s long-time collaborator, architect Sebastian Behmann – the facades of Harpa Reykjavik Concert Hall and Conference Centre. Another major strain of their investigation concerns the possibilities of combining complex polyhedrons into compound structures that contrast with the traditional forms of modern architecture and the built environment.

Eliasson described Thorsteinn as having a gift, ‘an ability to think spatially – and this – without his thoughts being based on the dominant Cartesian or Euclidean space-time conception. . . . I mean that he is able to construct a more complex dimensional shape in his thoughts alone, with high precision – while discussing and developing it.’

Today, the geometry team at Studio Olafur Eliasson continues to be a major driver behind studio projects, engaging in research into curves, polyhedrons, symmetry, and patterns, and providing the basis for major architectural projects, large-scale commissions, and smaller works.

Eliasson considers the various artworks rooted in geometrical studies as models of reality. Not as models that embody a certain truth, but models that offer alternatives to much mainstream architecture today and to how we think about our built and lived environments.

Sources

Olafur Eliasson, ‘Notes on my overlap with Einar Thorsteinn’, in Olafur Eliasson and Einar Thorsteinn, To the Habitants of Space in General and the Spatial Inhabitants in Particular (Vienna, 2002).

8 / 26

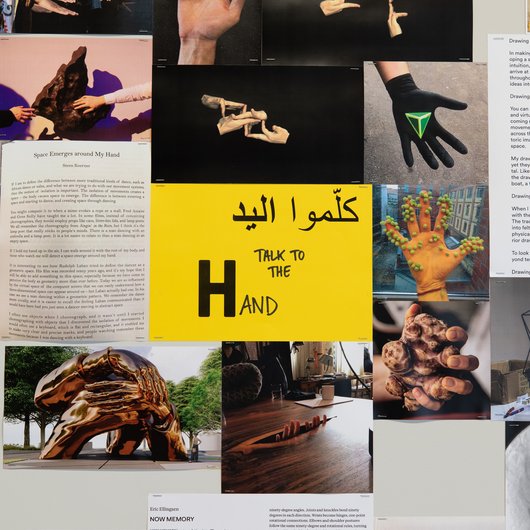

Hand(s)

Confined to a hospital bed after surgery, the choreographer Yvonne Rainer began composing dances for her hands. They were captured in her film Hand Movie, 1966, in which she flexes and relaxes her hand and moves her fingers together and apart, up and down. Rainer’s film shows that a hand can be the start of any dance – an idea that has also inspired the street dancer Steen Körner, who writes about space emerging around his hand, moving from the tips of the fingers along the arms, through the body, and out into the world: ‘The isolation of movements creates a space – the body causes space to emerge. The difference is between entering a space and starting to dance, and creating space through dancing.’

A hand is generally the point of origin of a drawing, according to Olafur Eliasson: ‘The dance of a hand across the paper combines muscle memory, cognitive skills, and motoric imagination.’

The sociologist Richard Sennett writes, ‘The body is ready to hold before it knows whether what it will hold is freezing cold or boiling hot. The technical name for movements in which the body anticipates and acts in advance of sense data is prehension.’

The hand can hold and shape. The mysterious clay forms in Nedko Solakov’s artwork Fear, 2002, reflect the artist’s fear of flying: the balls of clay, which he carried with him when he flew, were shaped by his clenched fists.

Sources

Steen Koerner, ‘Space Emerges around My Hand’, in Never Tired of Looking at Each Other – Only the Mountain and I (Beijing, 2012).

Olafur Eliasson, unpublished statement on drawing, 2014.

Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London, 2009).

9 / 26

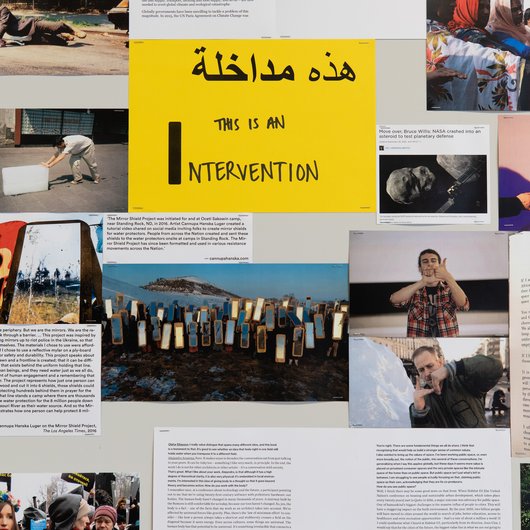

Intervention

An intervention can be as simple as staring into a mirror while walking through the city, as was done by the Institut für Raumexperimente (Institute for Spatial Experiments), the five-year experiment in arts education founded by Olafur Eliasson in 2009. Or it can be more complex, like an organised community action that short-circuits political, corporate, and social powers across local and national levels (Standing Rock, 2016–2017). As artist Cannupa Hanska Luger puts it, ‘As artists, we live on the periphery. But we are the mirrors. We are the reflective points that break through a barrier.’ Luger is a multidisciplinary artist and enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Lakota). In 2016, he created mirrored shields for protestors at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, in North Dakota, to support their efforts in blocking the construction of an oil pipeline that threatened their water supply.

The scene of intervention is often public space. The architect Alejandro Aravena pleads for more and better public spaces: ‘Public space has a huge, powerful capacity of redistribution – not of income, but of quality of life. . . . One way to measure a city is to look at what you can do in it for free.’

Writer and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes: ‘The market economy story has spread like wildfire. . . . But it is just a story we have told ourselves and we are free to tell another.’ Kimmerer, who describes herself as a mother, scientist, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, is a decorated professor who strives in her writings to bring together scientific and Indigenous knowledges to promote sustainability.

Intervention often entails working from within a system. Writer and ecological activist George Monbiot argues, ‘Because we are embedded in the systems we contest, and life is complicated, no one has ever achieved moral purity. . . . It is better to strive to do good, and often fail, than not to strive at all.’

Sources

Cannupa Hanska Luger, ‘Mirror Shield Project’, online at http://www.cannupahanska.com/mniwiconi

Alejandro Aravena, in conversation with Olafur Eliasson, ‘Reclaiming Cities’, in In Real Life (London, 2019).

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis, 2015).

George Monbiot, ‘Today, I Aim to Get Arrested. It Is the Only Real Power Climate Protestors Have’, The Guardian, 16 October 2019.

10 / 26

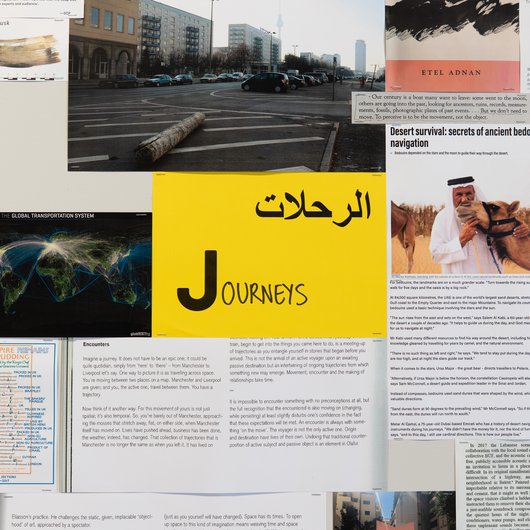

Journey

You, the visitor, have journeyed to this spot, to inhabit for a time this space, to encounter this exhibition and these artworks. In a different sense, each of the works in the exhibition has also journeyed to meet you: the works have their own trajectories and pasts and they bear witness to other histories.

For Berliner Treibholz (Berlin driftwood), 2009, the logs of wood that Olafur Eliasson distributed throughout the city were collected from the beaches of Iceland, which is famously devoid of large trees. They had arrived there from across the ocean, some having travelled thousands of kilometres. The cracked and bleached surfaces testify to this journey. ‘You can’t hold places (things, anything) still’, writes geographer Doreen Massey. ‘What you can do is meet up with them, catch up with where another’s history has got to “now”, and acknowledge that “now” as itself constituted by that meeting up.’

Abeer Seikaly’s Meeting Points, 2019, ‘is a working prototype for a reconfigurable composite material system . . . [made] in response to the design processes of Bedouin tent-making craft; communal practices of weaving and construction traditionally tasked to the Women of the tribe, the invisible architects in a patriarchal system’. The architect and designer asks, ‘How can cultural heritage remain relevant within a globalised society?’ In 2020, Eliasson met Seikaly through an online panel hosted by Reykjavik Global Forum – Women Leaders.

‘To perceive is to be the movement’, writes poet Etel Adnan. Her tender, precise, and expansive contributions to writing and painting during her lifetime have long resonated with the work we do at Studio Olafur Eliasson.

The Covid-19 pandemic may represent a journey that has left the world changed. ‘May our normal never be the same again’, writes philosopher and com-post-activist Bayo Akomolafe.

Sources

Doreen Massey, ‘Some Times of Space’ in Olafur Eliasson: The Weather Project (London, 2003).

Abeer Seikaly, artist’s statement on Meeting Points, 2019.

Etel Adnan, Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito, 1986).

Bayo Akomolafe, I, Coronavirus: Mother, Monster, Activist, online at https://www.bayoakomolafe.net/post/i-coronavirus-mother-monster-activist.

11 / 26

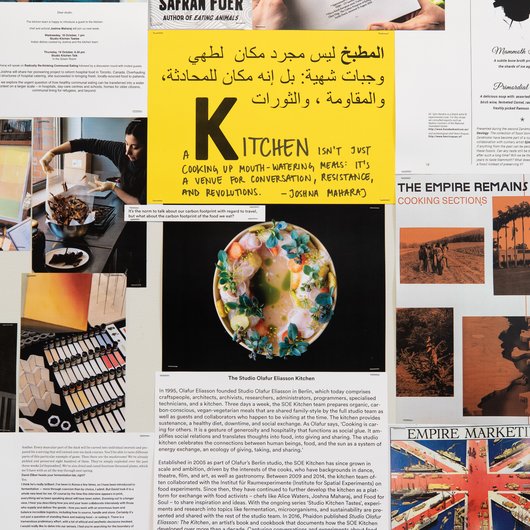

Kitchen

Through communal, organic, vegetarian/vegan meals served several days a week, the kitchen at Studio Olafur Eliasson plays a major role in fostering interdepartmental collaboration. It also periodically hosts experiments with food, workshops on topics like fermentation or baking with sourdough, and presentations by visiting food specialists, such as the chef and activist Joshna Maharaj, who presented her project for reforming the kinds of meals served at hospitals and other large public institutions.

The kitchen has also contributed to the studio’s efforts to reduce our carbon footprint by calculating emissions associated with meals and introducing more and more vegan recipes. One effective step for reducing carbon emissions is to decrease planetary consumption of meat and dairy, a goal supported by the EAT Lancet Commission Report. This does not, however, mean that everyone must become a vegetarian, as the novelist Jonathan Safran Foer explains: ‘Not eating animal products for breakfast and lunch has a smaller CO2e footprint than the average full-time vegetarian diet’, because the dairy-dependence of many vegetarians is responsible for considerable carbon emissions.

In the studio the kitchen also stands at the crossroads of food and art. The link between the two stretches back throughout history, in still lifes and vegetal patterns found in Western and Islamic art, but also in the work of contemporary artists. For example, Eliasson and the team have been experimenting with creating paint pigments from vegetable waste over the past few years. Some results were exhibited as part of the Sustainability research lab, 2020, in his exhibition Sometimes the river is the bridge, at Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo in 2020.

In a notably less vegetarian project, artist Theun Karelse created edible soup from a mammoth fossil, which raises fascinating questions about the way food can link us to a distant past. After experimenting with making a fossil broth, first by simply mixing fossilised bone fragments with water and stewing them, he developed a recipe for ‘mammoth soup’.

In the book The Empire Remains Shop, the artist group Cooking Sections looks at the British colonial legacy in, among others, a recipe for typically ‘British’ Christmas pudding made of ingredients whose origins span the far corners of its former global empire. The book also offers recipes for responding to the climate crisis, such as ‘drought salad’ and ‘tidal crispbread’. Through its materiality and narratives, food connects us to each other, to the wider world, and to otherwise bygone times.

Sources

Jonathan Safran Foer, We Are the Weather (New York, 2019).

Theun Karelse, Fieldguide to Next Doggerland (Amsterdam, 2015).

Cooking Sections, The Empire Remains Shop (New York, 2018).

12 / 26

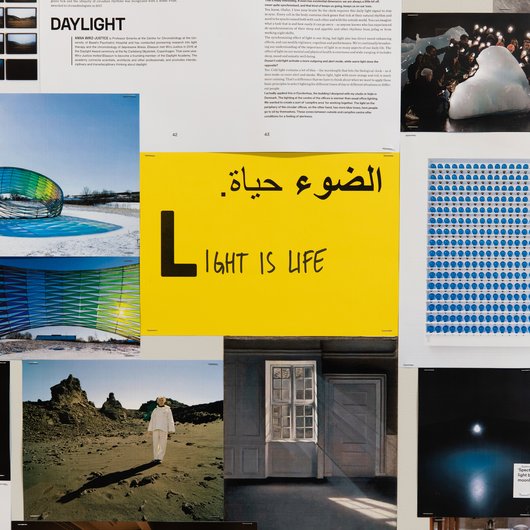

Light

Light plays a central role in Olafur Eliasson’s art, a fascination that stretches back to his childhood visits to Iceland during the summer, when oil for electricity was rationed: ‘A bell would ring and the electricity would go off. For the first second or so everything was pitch black. Then the windows lit up, because as soon as your eyes got used to . . . the darkness . . . light seemed to appear in the windows: the blue of dusk.’

Light affects everything we do. As chronobiologist Anna Wirz-Justice explains, ‘From the smallest bacteria, fungi and plants to flies and fish and mammals, living things all have a remarkably similar set of “clock genes” that generate an internal cycle of about twenty-four hours. . . . The biological clock that drives our daily rhythms receives light input from the outside world via the eye and the optic nerves. . . . [T]here’s a separate optic track leading from these [eye] cells directly to the biological clock – using light to provide non-visual information to the brain. Light has a surprisingly large number of effects that have nothing to do with our visual system – most importantly, acting as a synchronising agent to the circadian clock.’

Eliasson’s artworks turn attention to light as the basis for perception. He has used light as the main component of artworks, altering the lighting conditions of display, for example. In 2006, he created a light installation in the ceiling of one of the galleries of the Lenbachhaus, in Munich, where a series of Kandinsky paintings were on display (Lichtdecke Kandinsky, 2006). The lighting in the room shifted fluidly between light temperatures that mimicked the daylight at six different geographical locations, in order to question the idea that museum lighting is ‘neutral’.

The apparent path of the sun through the sky has also served as inspiration for structures, like Dagslyspavillon, 2007, whose latticework structure traces the path of the sun over the particular site where it is located.

Eliasson’s focus on light was originally motivated by an interest in dematerialising the art object: ‘I was interested in making an empty room atmospheric.’

Improving access to high-quality light is a major motivation for Eliasson’s Little Sun project, a social business that distributes solar lamps in areas of the world that lack consistent electricity.

Sources

Olafur Eliasson, in conversation with Tor Nørretranders, in Light! On Light in Life and the Life in Light (Klampenborg, 2015).

Anna Wirz-Justice, in conversation with Olafur Eliasson, ‘Daylight’, in Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life (London, 2019).

Design Milk Staff, ‘MDW19: A Sit-Down with Olafur Eliasson at Milan Design Week’, Design Milk, 8 May 2019.

13 / 26

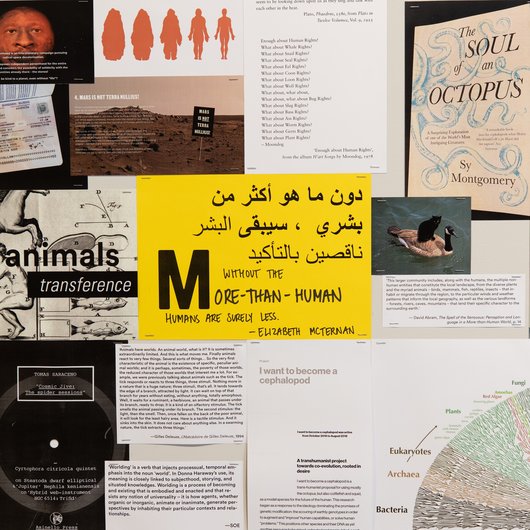

More-than-human

The phrase ‘more-than-human’ was coined in 1996 by ecologist David Abram, who wrote, ‘This larger community includes, along with the humans, the multiple nonhuman entities that constitute the local landscape, from the diverse plants and the myriad animals – birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, insects – that inhabit or migrate through the region, to the particular winds and weather patterns that inform the local geography, as well as the various landforms – forests, rivers, caves, mountains – that lend their specific character to the surrounding earth.’

The term has been deployed in many other works, spanning environmental science, art, and philosophy. The more-than-human is explicitly additive and implies an along-withness. Philosopher, biologist, and feminist Donna Haraway, for example, writes, ‘Human genomes can be found in only about 10 percent of all the cells that occupy the mundane space I call my body; the other 90 percent of the cells are filled with the genomes of bacteria, fungi, protists, and such, some of which play in a symphony necessary to my being alive at all, and some of which are hitching a ride and doing the rest of me, of us, no harm. I am vastly outnumbered by my tiny companions; better put, I become an adult human being in company with these tiny messmates. To be one is always to become with many.’

The more-than-human elevates objects, systems, landscapes, and other non-biological natural phenomena to that same conceptual realm of care and mutuality, and helps to shift those discourses away from biocentrism. In an article titled ‘About a Stone’, environmental researcher Hugo Reinert writes, ‘Claims about the nature of life as a superordinate domain also warrant hesitation. . . . Claims of this sort risk cutting the world as they assemble it, like a knife. . . . It is all the more vital to question the paradigms that subtend it and produce not just nonhuman life but also nonlife as domains of control, use, modification, and productive investment.’

The more-than-human is an inclusive umbrella for the inanimate and inorganic alongside the living, and demonstrates that the non-living, whether winds or rocks or complex river systems or bottle caps, are also essential agents in the world’s social and political entanglements. Without the more-than-human, humans are surely less.

Sources

David Abrams, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World (New York, 1996).

Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis, 2007).

Hugo Reinert, ‘About a Stone: Some Notes on Geologic Conviviality’, in Environmental Humanities 8, no. 1 (May 2016).

14 / 26

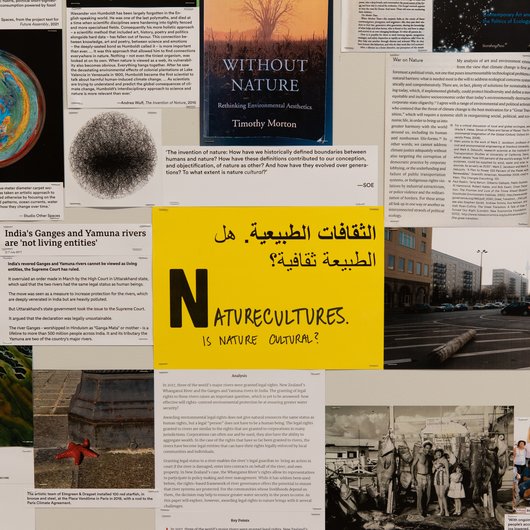

Naturecultures

Naturecultures, a term that has been used by a number of thinkers in recent years, was first coined by the philosopher, biologist, and feminist Donna Haraway. It suggests that there is no pure state of nature outside human activity and that culture is a force of nature in itself. In other words, ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ cannot be disentangled. The mainstream separation of the two concepts originates in European philosophy and science from the Enlightenment onwards. More recently, there has been a growing movement among philosophers, anthropologists, and other scholars to criticise this compartmentalisation as a fiction, most notably by philosopher and sociologist Bruno Latour and feminist scholar of science and technology María Puig de la Bellacasa.

Puig de la Bellacasa writes,‘“Naturecultures” cosmologies require a form of ethical commitment that learns from the decentring of the human.’

Naturecultures is a fundamental theme for Olafur Eliasson, especially in artworks that collapse the divide between inside and outside. In 2021, for example, Life, at Fondation Beyeler, near Basel, Switzerland, opened up the existing museum space to the surrounding pond and park, allowing the water to flow into the galleries, along with the animals and plants living there. With this intervention, Eliasson aimed to complicate the perceived borders of the exhibition. Where does the art end and the ‘real’ world begin? This can be both a generative and an unanswerable question.

Novelist Josefine Klougart observes, ‘Instead of looking at poetry, philosophy, mathematics and science as things that set us apart from nature, we have to start seeing them as nature’s way of reflecting on itself.’

Breaking down the conceptual barrier between nature and culture entails reconsidering how we think about conservation and environmentalism and, more broadly, our responses to the climate crisis. According to the United Nations, ‘The law has seen the beginning of an evolution toward recognition of the inherent rights of Nature to exist, thrive and evolve. . . . Rights of Nature is grounded in the recognition that humankind and Nature share a fundamental, non-anthropocentric relationship given our shared existence on this planet . . . ’

For Future Assembly, 2021, Studio Other Spaces – the office for art and architecture founded by Eliasson and Sebastian Behmann – investigated the emergence of the ‘rights of nature’, along with their implementation and concomitant struggles, in various places around the globe.

Sources

Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003).

María Puig de la Bellacasa, ‘Ethical Doings in Naturecultures’, in Ethics Place and Environment, June 2010.

Josefine Klougart, in conversation with Olafur Eliasson, ‘We Are Nature’, in Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life (London, 2019).

United Nations, ‘Rights of Nature, Law, Policy and Education’, Harmony with Nature website, http://www.harmonywithnatureun.org/rightsOfNaturePolicies/

15 / 26

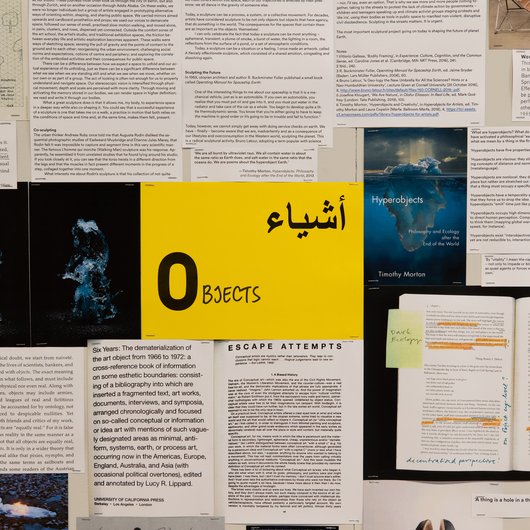

Objects

‘What philosophy shares with the lives of scientists, bankers, and animals is that all are concerned with objects’, writes Graham Harman. To this list of protagonists, one might add artists – even those who have strived to dematerialise objects. In the words of art critic Lucy Lippard, ‘Conceptual art, for me, means work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious and/or “dematerialized”.’ Harman points out that objects include entities that are neither physical ‘nor even real’ – dragons, square circles, and utopias are just as much objects as sailboats, atoms, and telephone poles. According to the so-called object-oriented ontology that Harman defined, the relationships that objects have with each other are as generative as their relationships with humans, if not more so.

‘For decades’, Olafur Eliasson writes, ‘artists have considered sculpture to be not only objects but objects that have agency, that do something in the world.’ They are objects that exhibit, in the words of political theorist Jane Bennett, ‘Thing-Power: the curious ability of inanimate things to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle.’

In art an object can be the ever-changing spout of a water fountain illuminated by a strobe light, a cloud, or a relationship between two trees. It can also be an idea or an unthought thought. Where, then, are the limits of objects? Is a void an object? Is climate change an object?

Philosopher Timothy Morton proposes the notion of the ‘hyperobject’ to refer to things like climate change, which are so much vaster than objects and yet must be treated as such. ‘Hyperobjects’, he writes, ‘do not manifest at a specific time and place but rather are stretched out in such a way as to challenge the idea that a thing must occupy a specific place and time.’

Sources

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object (Winchester, UK, 2011).

Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (Oakland, 1997).

Olafur Eliasson, ‘Becoming Co-sculptural’, in Modern Sculpture: Artists in Their Own Worlds, edited by Douglas Dreishpoon (Oakland, 2022).

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Economy of Things (Durham, 2010).

Timothy Morton, ‘What Does Hyperobjects Say?’ Ecology Without Nature, 28 December 2012: http://ecologywithoutnature.blogspot.com/2012/12/what-does-hyperobjects-say.html

16 / 26

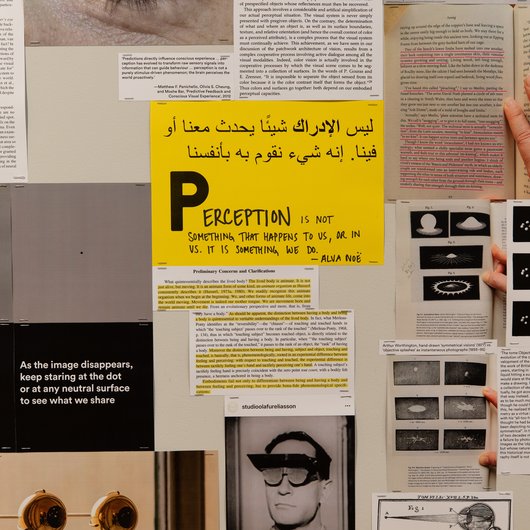

Perception

‘The eye is not a camera that forms and delivers an image, nor is the retina simply a keyboard that can be struck by fingers or light,’ writes psychologist J. J. Gibson.

The question of perception is central to Olafur Eliasson’s art practice. In his understanding, perception ‘is not about receiving information from the world – it is about doing. We are co-producers of what we perceive’. Or as philosopher Alva Noë and others argue, ‘[V]ision is a capacity of the whole situated animal. . . . [S]eeing is the temporally extended activity of visually exploring the environment.’

Anthropologist and dancer Natasha Myers points out that ‘your body does not end at the skin. . . . Your imagination generates more than mere mental images; its reach extends through your entire sensorium. Simultaneously visual and kinesthetic, imaginings carry an affective charge. . . . Perceptual experiments can rearticulate your sensorium. And by imagining otherwise, and telling different stories, you can open up new sensible worlds.’

Eliasson approaches these ideas by exploring optical illusions, moiré patterns, after images, reflections, and light phenomena, focusing on what we contribute to our perceptions, what the eye and brain bring to what we see. He is interested moreover in how animals perceive the world and the ways in which language shades our perception of colour, and in questioning the dominance of visuality in culture by opening up art experiences to include smell, taste, and tactility.

Sources

J. J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Abingdon, 1979).

Matthew F. Panichello et al., ‘Predictive Feedback and Conscious Visual Experience’, Frontiers in Psychology 3, no. 620, 2012.

Alva Noë, Luiz Pessoa, and Evan Thompson, ‘Beyond the Grand Illusion: What Change Blindness Really Teaches Us About Vision’, Visual Cognition 7, nos. 1–3, 2000.

Natasha Myers, ‘A Kriya for Cultivating Your Inner Plant’ (Vancouver, 2014).

17 / 26

Quantifiability

What does one tonne of CO2 look like? How can we make something as abstract as the weight of a gas tangible? Can doing so motivate action and effect change? Olafur Eliasson argues that science often misses the mark in motivating action, because of its emphasis on quantifiable data that is often abstract to the broad public. Art, according to him, can be more effective in reaching people by enabling direct experiences and bringing them into tangible contact with seemingly distant realities: ‘Although it is clearly important to ground action in knowledge and rational thought, we also need to understand the central role of our experiential system in motivating action.’

At the same time, ‘we need to move beyond the failure-success dichotomy’, Eliasson argues, ‘to embrace new, non-quantifiable criteria for what is a good work of art’. For him this is about supporting facets of our societies that are not quantifiable, that cannot be measured or capitalised upon. In modern cultures propelled by answer-driven measurement and technological advancement, preferred concepts are often those that can be made tidy by omitting outliers in favour of a legible model, while lived experience is often dismissed as too messy. In reality, anomalies are the norm, and contradictions the rule rather than the exception. We need to embrace new – and many! – narratives of the unquantifiable. This too is an area where art is particularly relevant – where we can propose that, in the words of Édouard Glissant, ‘we are integral to this constellation of humanities. That this does not turn into a system. That the totality is forever totalizing. That the All is not closed nor sufficient. This is the living world. . . . to dream the world is not to live it. For us beauty does not grow from the dream, it explodes in the entanglement.’

Sources

Olafur Eliasson, ‘The Power of Culture to Prompt Action’, in United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2016 ‘Human Development for Everyone’, online at https://hdr.undp.org/content/power-culture-prompt-action.

Édouard Glissant, ‘Measure, Immeasurability’ in Treatise on the Whole-World (Liverpool, 2020).

18 / 26

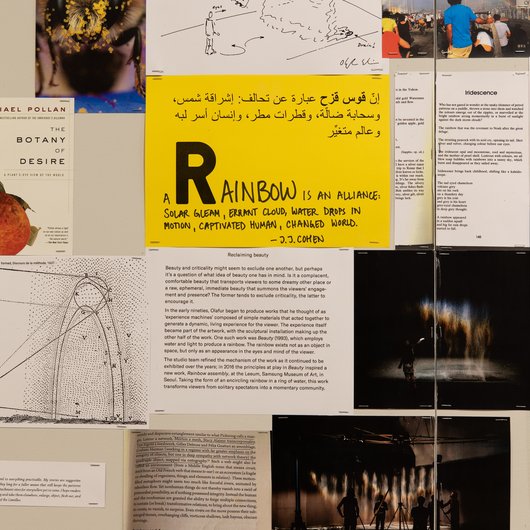

Rainbow

In Olafur Eliasson’s words:

‘A rainbow reflects where you are in relation to the sun. For you to see it, you must be standing with the sun behind you at a relatively low position, and the drops of water must be somewhere in the sky in front of you, near or far away. Light refracted by the droplets hits your eyes at an angle of 42 degrees. Your eye, the sun, the drops of water – these three elements work together to conjure the rainbow.

‘Geometrically speaking, a rainbow is actually a circle. If the earth were not in the way, if there were no horizon blocking your view, you would see the whole round rainbow as a perfect circle wrapping around you, with your eye at its centre. Two people standing even a few metres apart will perceive two different rainbows, each oriented to their own perspective. We can never see the other person’s rainbow.

‘You could almost say that a rainbow, as an ephemeral phenomenon, confirms my existence. If there is a rainbow, then there must be an I who is seeing it.

‘In the hurly-burly of everyday existence, the generosity of the rainbow lies in its unexpected appearance. It is a small miracle when the position of the sun, adequate weather conditions, and your eyes – otherwise focusing on your busy life – align to create a rainbow. This may allow you to pause to celebrate the fleeting moment of trajectories meeting up. It is like nature offering a surprise party, while allowing us the pleasure of being a co-host.’

—Olafur Eliasson, statement for the exhibition Your light spectrum and presence, at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles, 5 February–2 April 2022

19 / 26

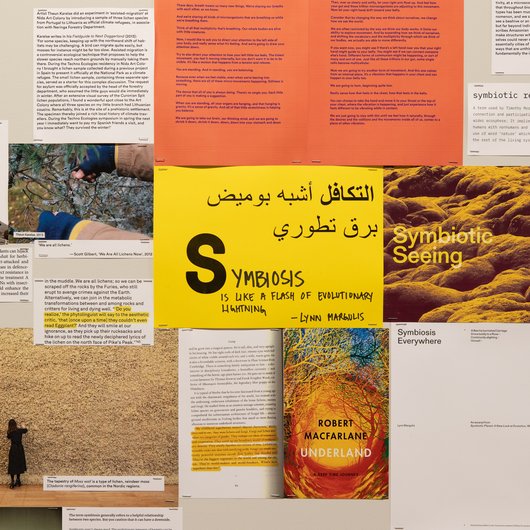

Symbiosis

Symbiosis ‘is the phenomenon in which organisms of different species live together in close association, resulting in a raised level of fitness for one or more of the organisms’, write researchers L. Bull and T. C. Fogarty. The scientist Lynn Margulis spent her professional life researching this phenomenon, seeing it as fundamental to the evolution of life on planet earth: ‘I think that throughout biological history, fusion of different organismal types has been much underestimated as an evolutionary phenomenon’. Inspired by Margulis’s radical ideas, Olafur Eliasson called his 2020 exhibition at Kunsthaus Zürich Symbiotic seeing. The accompanying catalogue contained texts by Margulis, Donna Haraway, Josefine Klougart, and others.

One of the classic examples of symbiosis in nature is lichen, which is made up of a moss and an algae or cyanobacteria living together. According to biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, lichen ‘remind us of the enduring power that arises from mutualism, from the sharing of the gifts carried by each species’. But as evolutionary biologist Nancy Moran reminds us, not all symbiosis is good for the host: ‘The bacteria might kill the host, so that the host corpse will disperse microbes.’

We all exist in symbiotic relationships with others, whether it is with other humans in society, with soil and with plants via agriculture, or with the bacteria that live in our gut. Artist Ally Bisshop explains: ‘Within each of our “human” bodies are 10–100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells that make up our microbial complement. This living mass within us is known as our microbiome. The microorganisms that make up our microbiome are not supplemental to our body, but a living part of it, without which we would cease to be. . . . We are multiple. The rhythm of our own being already unfolds myriad nonhuman durations. We are always already more than human.’ There is currently a lot of research into the relationship between the bacteria in our stomach and our brain, the ‘gut–brain axis’, which is hypothesised to have major effects on our mental state and health.

Symbiosis is therefore also a question of the boundaries of our self, of our bodies. With this notion, one can question the modern, Western conception of a person as a discrete being, an individual existing beyond and independently of the many relationships that we are part of.

Anthropologist Anna Tsing writes: ‘What if our indeterminate life form was not the shape of our bodies but rather the shape of our motions over time? Such indeterminacy expands our concept of human life, showing us how we are transformed by encounter.’

Sources

L. Bull and T.C. Fogarty, ‘Artificial Symbiogenesis’, Artificial Life 2, no. 3, 1995.

Lynn Margulis, interview, Sputnik Observatory, 2017.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis, 2015).

Nancy Moran, ‘An Explorer of Life’s Deepest Partnerships’ (interview). Quanta Magazine. 17 September 2015.

Ally Bisshop, Possible Vehicles for Time Travel (Berlin, 2018).

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, 2021).

20 / 26

Trust

We need trust, says philosopher Onora O’Neill, ‘because we have to be able to rely on others acting as they say that they will, and because we need others to accept that we will act as we say we will’. This can be true on the level of society at large, where we must trust in institutions to make informed decisions to safeguard the population, and to maintain infrastructure, so that we are not swallowed by a sinkhole when walking down the street, or something as quotidian as how we navigate traffic. As Olafur Eliasson puts it, ‘There is an unstated contract: we agree that living is better than dying. . . . We have faith that the car coming towards us isn’t just going to cross over to our side, because we assume that the driver also cares about living. It’s interesting that there are common beliefs and contracts everywhere we go, confidence that something is actually going to work out, even though we can’t know this for sure.’

Trust is very much a question of a well-functioning public sector, an idea which is often neglected in economics, but which thinkers like economist Mariana Mazzucato have been arguing in favour of giving attention to: ‘I believe public value should be seen as an objective, and one the pursuit of which is characterised by an open process of debate – involving citizens.’ Mazzucato shows how governments and state support drive innovation.

Trust is not only about group dynamics. In spaces of creativity, trust in process and trust in oneself to be vulnerable are also essential. As feminist philosopher María Lugones once wrote: ‘Playfulness is, in part, an openness to being a fool, which is a combination of not worrying about competence, not being self-important, not taking norms as sacred and finding ambiguity and double edges a source of wisdom and delight.’

At the same time, there is no trust without uncertainty.

Sources

Onora O’Neill, ‘A Question of Trust’, Reith Lectures, 2002, online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p00gpzfq

Olafur Eliasson, Turning Thinking into Doing into Art: Four Lectures in Addis Ababa (Berlin, 2015).

María Lugones, ‘Playfulness, “World”-Travelling, and Loving Perception’ (1987), in Feminist Philosophy of Mind (Oxford, 2022).

Mariana Mazzucato, in conversation with Olafur Eliasson, ‘Trust’, in Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life (London, 2019).

21 / 26

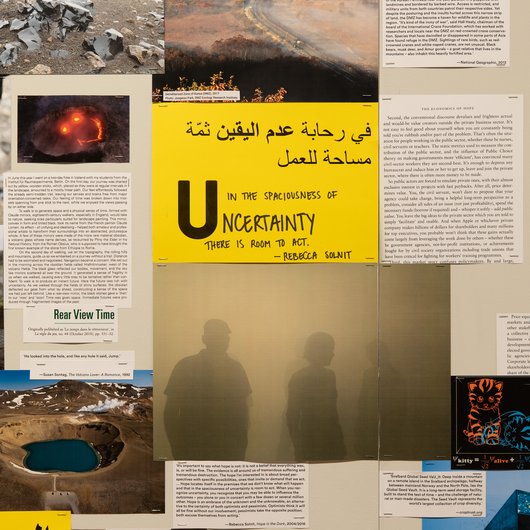

Uncertainty

In art, states of uncertainty can be generative and open up for creativity, although these states, in Olafur Eliasson’s words, ‘don’t fit the success criteria of today’. Attempts to reduce uncertainty can limit our imagination and cause ‘the critical potential of doubt [to] disappear’. For some time, Eliasson has wanted to establish a garden at his studio – not a patch of greenery with soil and plants, but a space for creative work to grow, unhampered by deadlines and budgets that place constraints and demands in equal measure. This garden is a space for ‘slow work, for weirdness, friction, and uncertainty, for things that can be intuited but not (yet) fully understood. It is a space of sound and movement exercises. Gardening requires letting go, listening, not knowing, staying inquisitive, saying more yes than no, and thinking about why, not only how.’

‘Because humans have a great need for predictability, uncertainty can be uncomfortable’, write researchers Debika Shome and Sabine Marx while discussing uncertainty in climate science. ‘Uncertainty can lead to anxiety.’

But hope may also spring from uncertainty. The author and activist Rebecca Solnit, whose writings keep inspiring us at the studio, says: ‘Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. . . . Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists take the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting.’

As the author Virginia Woolf wrote in her journal on 18 January 1915, ‘The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think.’

Sources

Debika Shome and Sabine Marx, ‘The Psychology of Climate Change Communication’ (New York, 2009): http://guide.cred.columbia.edu/pdfs/CREDguide_full-res.pdf

Olafur Eliasson, Your Exhibition Guide, digital application, 2014

Olafur Eliasson, On gardening, not published.

Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark (Chicago, 2004/2016).

Rebecca Solnit, ‘Woolf’s Darkness: Embracing the Inexplicable’, The New Yorker, 24 April 2014. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/woolfs-darkness-embracing-the-inexplicable.

22 / 26

Volcano

Iceland’s roughly 130 volcanoes have formed its landscape over millennia. The resulting black-sand beaches, steaming pumice fields, and geysers continue to be subjects of Icelandic lore and international fascination. Olafur Eliasson, who spent much of his childhood in Iceland, has travelled there frequently over the years to photograph the landscape and geography of the country, especially its volcanoes.

Volcanoes exist at the threshold between the inside and outside of the planet. Their periodic eruptions launch a rock cycle that brings the molten material from deep beneath Earth’s crust to its exterior. This sudden reconfiguration of inside and outside is also a focal point for the imagination and for metaphor. The earth below our feet is in constant transformation at a timescale that is mostly imperceptible to humans, except for these occasional sites of rupture, which, in many mythologies, have been imagined as portals to underworlds. In a way this is true – volcanoes are windows into the otherwise withdrawn worlds of rocks. Staring down into a lava crater can remind us that rocks and their constituent elements are far from inert; they are not just rocks, but rock-beings that have their own agencies, deep-time histories, and futures. They are dynamically entangled with the spheres of living beings, as they spew forth to form new landmasses, obliterate life-worlds, nourish new life, inspire legends, and sometimes even go so far as to alter the global climate.

Numerous artworks by Eliasson – including Lava floor, 2002, and Your disappearing garden, 2011 – employ volcanic rocks such as obsidian, pumice, and basalt as material or as inspiration. These rocks presented in exhibition spaces often have an uncanny quality to them – a material meeting of the familiar and the strange.

23 / 26

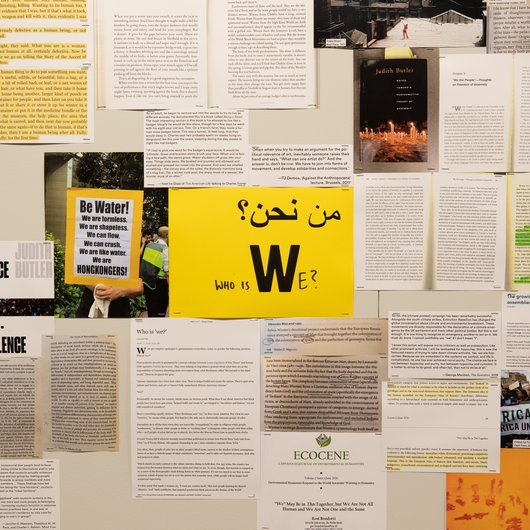

We (and water)

What do we mean when we use the word we? And where do we draw the boundaries of we? According to the scientists Jennifer S. Mascaro, Thaddeus W. W. Pace, and Charles L. Raison, ‘It has been known since time immemorial that people tend to favor other individuals they view as being similar to themselves and/or who belong to one’s in-group. . . . Oxytocin actually enhances the distinction between in-group and out-group by making people more cooperative and caring towards in-group members and more defensive towards out-group members …’ What, then, is the extent of our in-group identification? Is it friends? Family? Neighborhood? Profession? Party? Religion? Race? Nation? Species? Or are we earthlings? And if so, do we consider the other animals, plants, and rocks to be earthlings as well, and part of our more-than-human we?

When anyone asks what one person can do, art historian T. J. Demos argues, ‘Don’t be one. We have to join into forms of movement, and develop solidarities and connections.’

‘We are formless’, a slogan from protests in Hong Kong proclaimed. ‘We are shapeless. We can flow. We can crash. We are like water.’

Recent pandemic lockdowns have inspired new ways of being alone together, as was done by a group of dancers who revisited choreographer Trisha Brown’s Roof Piece in the form of a reprise, called Room/Roof Piece. Roof Piece was originally performed in 1971 outdoors and at a distance, from one rooftop to another, in New York City. In 2020 the individual dancers performed the work in the isolation of their own homes via their screens, as a way for them to stay creatively connected during the long period of ‘social distancing’.

And there are intergenerational wes. As the writer Saidiya Hartman argues, ‘Every generation confronts the task of choosing its past. . . . The past depends less on “what happened then” than on the desires and discontents of the present. Strivings and failures shape the stories we tell.’

Sources

Jennifer S. Mascaro, Thaddeus W. W. Pace, and Charles L. Raison, ‘Mind Your Hormones’, in Tania Singer & Matthias Bolz, eds., Compassion: Bridging Theory and Practice, 2013.

T. J. Demos, ‘Against the Anthropocene’ lecture, Brussels, 2017.

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York, 2007).

24 / 26

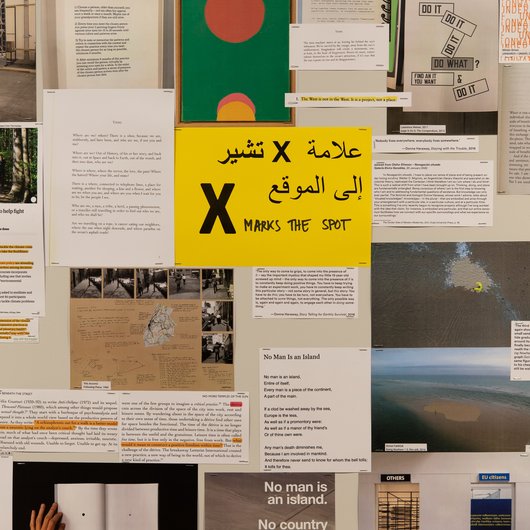

X marks the spot

An expression from English-language popular culture, ‘X marks the spot’ refers to the practice of marking a pirate map with an X to show the location of buried treasure.

‘Where are we? where?’ asks poet and artist Etel Adnan. What would it be like to be there where you are, fully present?

Writer Jon Kabat-Zinn discusses ways of cultivating mindfulness in your daily life, to ‘experience what you are doing in a fully embodied way as you are actually doing it; in other words, being fully present, as best you can, moment by moment, for the unfolding of your life’. At Studio Olafur Eliasson, we’ve been interested in compassion and mindfulness ever since we hosted the three-day workshop ‘How to Train Compassion’ in 2011, an event organised by social neuroscientist Tania Singer that included, among others, the Buddhist teachers Joan Halifax, Matthieu Ricard, and Barry Kerzin.

A spot can be a place of presence but it can also be a void or a blind spot. Philosopher Michel Bitbol argues that the blind spot is the position from which you view something: ‘What is not seen . . . is the seer, the one who sees, the one who is seeing.’

Olafur Eliasson writes: ‘Walter D. Mignolo, an Argentinian literary theorist and specialist on decolonial theory, rephrased the Cartesian I think therefore I am as I am where I do and think. . . . Thinking, doing, and place are fundamentally entangled. Being conscious of where I am is the first step to knowing who I am and to addressing fundamental questions of existence. But knowledge can only ever be partial. The feminist and biologist Donna Haraway . . . talks about “situated knowledges”: knowledges – in the plural – that are embodied and arise through your entanglement with a particular site, in a particular culture, and at a particular time.’

Sources

Etel Adnan, There: In the Light and the Darkness of the Self and the Other (New York, 1997).

Jon Kabat-Zinn, Full Catastrophe Living (New York, 1990).

Michel Bitbol, Never Known But Is the Knower (Berlin, 2014).

Olafur Eliasson, excerpt from the artist’s statement on the exhibition Navegacíon situada, at Galería Elvira González, 20 January–2 April 2022.

25 / 26

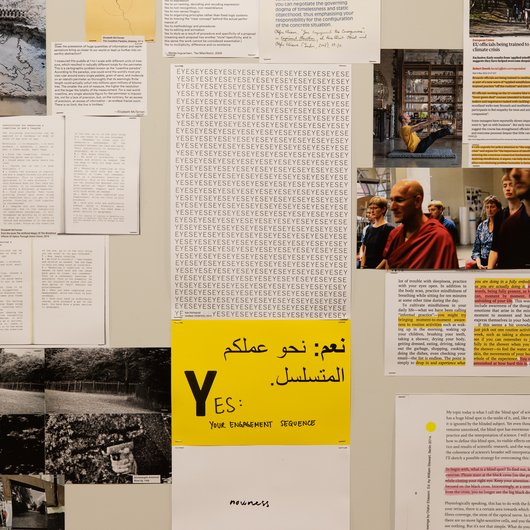

Yes

‘Yes’ reflects Olafur Eliasson’s belief in the importance of affirmation for engaging with the world. The idea that ‘your engagement has consequences’ has long motivated the artist. By this he means that people co-produce the world through their actions.

In his essay ‘You Engagement Has Consequences’, Eliasson writes: ‘The relativity that temporal engagement inevitably introduces should, for scientific laboratory purposes, be given a name: I suggest “YES” (Your Engagement Sequence). YES attunes our attention to time, movement and changeability. It makes relative what is often considered to be true. Whenever a so-called truthful statement is made, you have to add YES in order to relate to, see through and make use of the statement. By regarding YES as a central element of our perceptions, you can negotiate the governing dogma of timelessness and static objecthood, thus emphasising your responsibility for the configuration of the concrete situation.’

Mette Ingvartsen writes in her ‘Yes Manifesto’:

Yes to redefining virtuosity

Yes to ‘invention’ (however impossible)

Yes to conceptualizing experience, affects and sensation

Yes to materiality and body practice

Yes to expression

Yes to un-naming, decoding and recoding expression

Yes to non-recognition, non-resemblance

Yes to non-sense/illogics

Yes to organizing principles rather than fixed logic systems

Yes to moving the ‘clear concept’ behind the actual performance of

Yes to methodology and procedures

Yes to editing and animation

Yes to style as a result of procedure and specificity of a proposal (meaning each proposal has another ‘style’/specificity, and in this sense the work cannot be considered essentialist.)

Yes to multiplicity, difference and co-existence

Sources

Olafur Eliasson, ‘Your Engagement Has Consequences’, in Experimental Marathon, eds. Hans Ulrich Obrist and Olafur Eliasson (London, 2007).

Mette Ingvartsen, ‘Yes Manifesto’, 2005, online at https://www.metteingvartsen.net/performance/5050/.

26 / 26

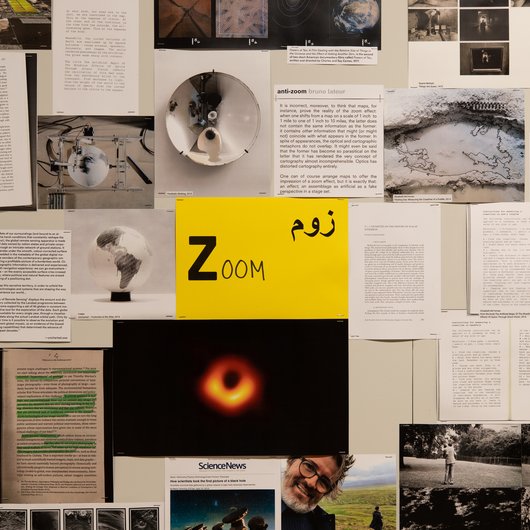

Zoom

Charles and Ray Eames’s 1977 film Powers of Ten famously attempted to visualise both the scale of the universe and that of the microscopic world by moving first outwards by degrees in scale and then inwards. In the age of Google Earth and spy satellites, this activity has become a commonplace way of navigating cities and countries. At the same time, it is also a tool of power and violence often wielded by nation-states. Philosopher and sociologist Bruno Latour argued against the false sense of mastery behind this act of shifting scale, since ‘levels of reality do not nestle one within the other like Russian dolls. . . . It is incorrect, moreover, to think that maps, for instance, prove the reality of the zoom effect: when one shifts from a map on a scale of 1 inch to 1 mile to one of 1 inch to 10 miles, the latter does not contain the same information as the former: it contains other information that might (or might not) coincide with what appears in the former.’